The Gadarene Demonaic and Azazel’s Goat

a comparative analysis of the transference of impurity

The Biblical and Talmudic Texts

I’ll begin with by providing the texts from the Torah, the Talmud, and the Gospels. Note: for the verses from the Torah and the rest of the Hebrew Bible, I always choose to use Sefaria as my source, over any Christian source.

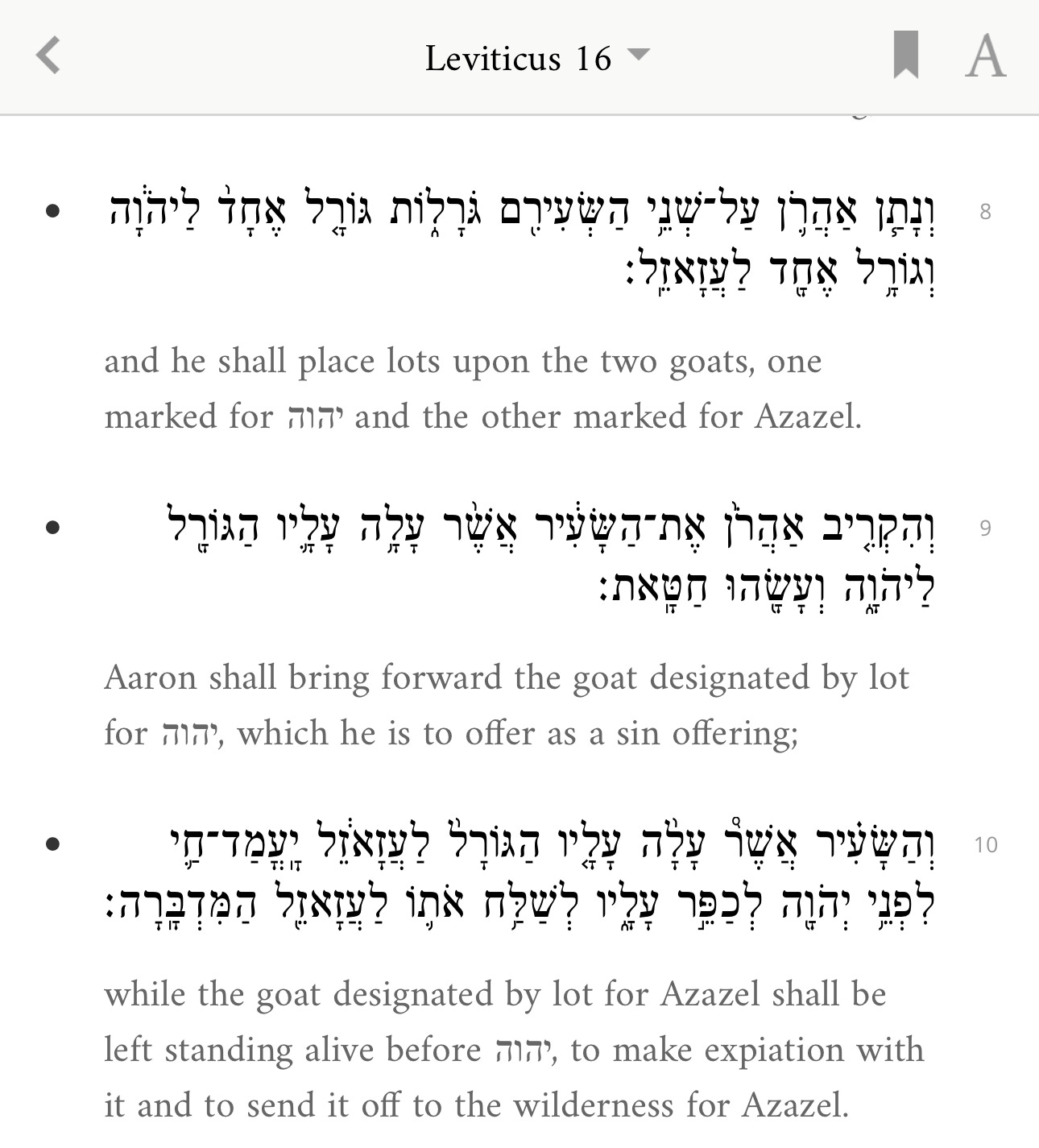

Leviticus 16:8-10, 21-23 :: Azazel’s Goat

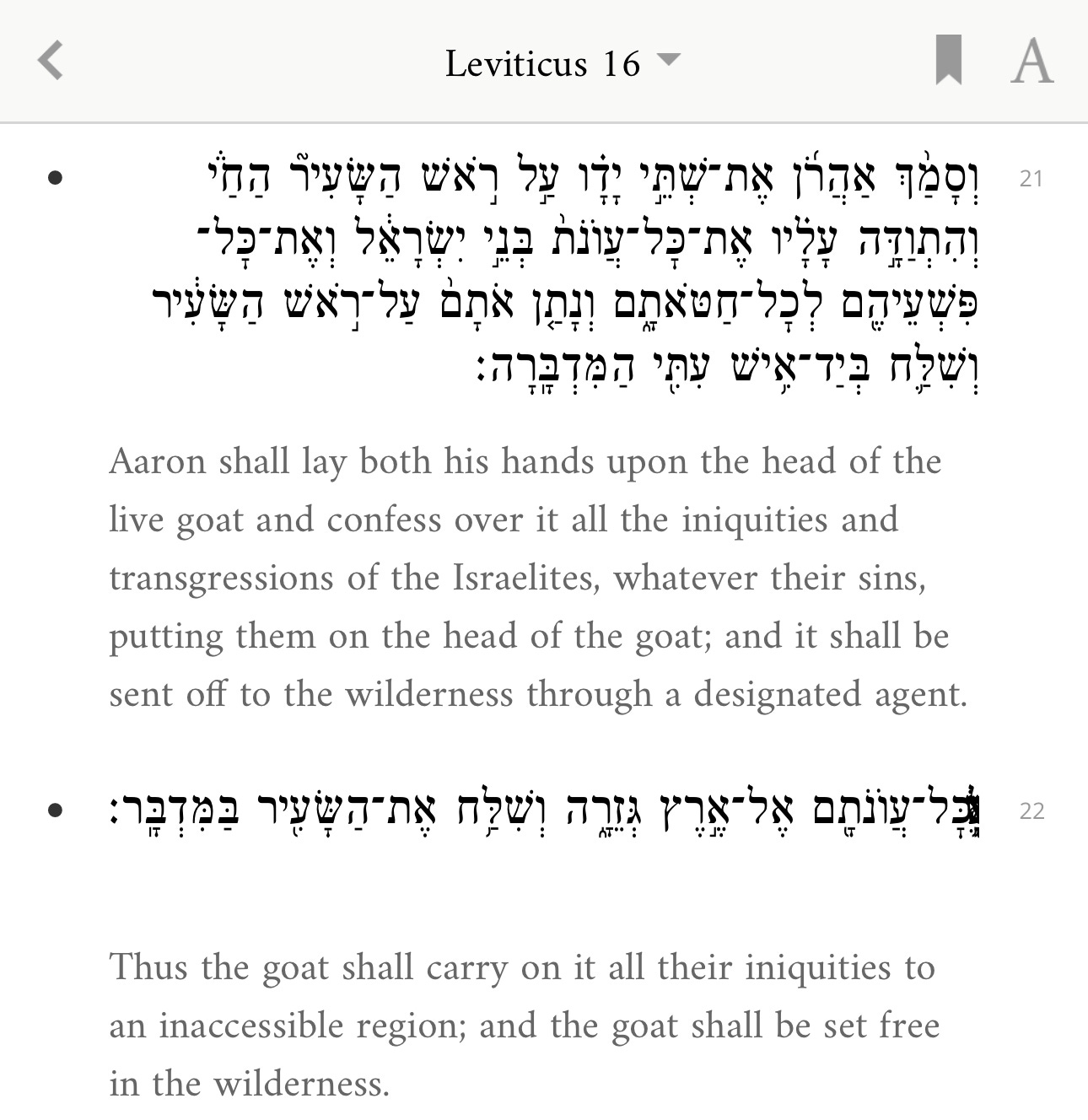

Yoma 67a Talmud Tractate :: Discussion of Azazel’s Goat

Matthew 8:28–34 :: Two Demon-Possessed Men Healed

28 When he arrived at the other side in the region of the Gadarenes, two demon-possessed men coming from the tombs met him. They were so violent that no one could pass that way. 29 “What do you want with us, Son of God?” they shouted. “Have you come here to torture us before the appointed time?” 30 Some distance from them a large herd of pigs was feeding. 31 The demons begged Jesus, “If you drive us out, send us into the herd of pigs.” 32 He said to them, “Go!” So they came out and went into the pigs, and the whole herd rushed down the steep bank into the lake and died in the water. 33 Those tending the pigs ran off, went into the town and reported all this, including what had happened to the demon-possessed men. 34 Then the whole town went out to meet Jesus. And when they saw him, they pleaded with him to leave their region.

Mark 5:1–20 :: A Demon-Possessed Man Healed

1 They went across the lake to the region of the Gerasenes. 2 When Jesus got out of the boat, a man with an evil spirit came from the tombs to meet him. 3 This man lived in the tombs, and no one could bind him any more, not even with a chain. 4 For he had often been chained hand and foot, but he tore the chains apart and broke the irons on his feet. No one was strong enough to subdue him. 5 Night and day among the tombs and in the hills he would cry out and cut himself with stones. 6 When he saw Jesus from a distance, he ran and fell on his knees in front of him. 7 He shouted at the top of his voice, “What do you want with me, Jesus, Son of the Most High God? Swear to God that you won’t torture me!” & For Jesus had said to him, “Come out of this man, you evil spirit!” 9 Then Jesus asked him, “What is your name?” 10 “My name is Legion,” he replied, “for we are many.” And he begged Jesus again and again not to send them out of the area. 11 A large herd of pigs was feeding on the nearby hillside. 12 The demons begged Jesus, “Send us among the pigs; allow us to go into them.” 13 He gave them permission, and the evil spirits came out and went into the pigs. The herd, about two thousand in number, rushed down the steep bank into the lake and were drowned. 14 Those tending the pigs ran off and reported this in the town and countryside, and the people went out to see what had happened. 15 When they came to Jesus, they saw the man who had been possessed by the legion of demons, sitting there, dressed and in his right mind; and they were afraid. 16 Those who had seen it told the people what had happened to the demon-possessed man--and told about the pigs as well. 17 Then the people began to plead with Jesus to leave their region. 18 As Jesus was getting into the boat, the man who had been demon-possessed begged to go with him. 19 Jesus did not let him, but said, “Go home to your family and tell them how much the Lord has done for you, and how he has had mercy on you.” 20 So the man went away and began to tell in the Decapolis how much Jesus had done for him. And all the people were amazed.

Luke 8:26–39 :: A Demon-Possessed Man Healed

26 They sailed to the region of the Gerasenes, which is across the lake from Galilee. 27 When Jesus stepped ashore, he was met by a demon-possessed man from the town. For a long time this man had not worn clothes or lived in a house, but had lived in the tombs. 28 When he saw Jesus, he cried out and fell at his feet, shouting at the top of his voice, “What do you want with me, Jesus, Son of the Most High God? I beg you, don’t torture me!” 29 For Jesus had commanded the evil spirit to come out of the man. Many times it had seized him, and though he was chained hand and foot and kept under guard, he had broken his chains and had been driven by the demon into solitary places. 30 Jesus asked him, “What is your name?” 31 “Legion,” he replied, because many demons had gone into him. And they begged him repeatedly not to order them to go into the Abyss. 32 A large herd of pigs was feeding there on the hillside. The demons begged Jesus to let them go into them, and he gave them permission. 33 When the demons came out of the man, they went into the pigs, and the herd rushed down the steep bank into the lake and was drowned. 34 When those tending the pigs saw what had happened, they ran off and reported this in the town and countryside, 35 and the people went out to see what had happened. When they came to Jesus, they found the man from whom the demons had gone out, sitting at Jesus’ feet, dressed and in his right mind; and they were afraid. 36 Those who had seen it told the people how the demon-possessed man had been cured. 37 Then all the people of the region of the Gerasenes asked Jesus to leave them, because they were overcome with fear. So he got into the boat and left. 38 The man from whom the demons had gone out begged to go with him, but Jesus sent him away, saying, 39 “Return home and tell how much God has done for you.” So the man went away and told all over town how much Jesus had done for him.

Comparative Summary of Biblical Texts

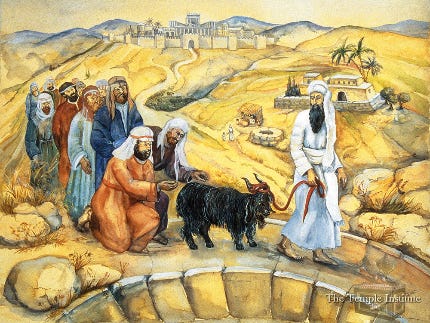

Artwork: The Scapegoat, by William Holman Hunt, (1854–1856), public domain.

The Leviticus 16 passage and the Yoma Tractates

In the Leviticus text G-d instructs the Israelites to designate a goat for a sin offering and another for expiation to Azazel. The Israelites lay their sins on the head of Azazel’s goat, then send it off into the wilderness. In the Yoma 67a and 67b tractates a lengthy discussion takes place regarding Azazel’s goat.

The written Torah comes fully alive when read in conjunction with the oral Torah. Traditionally, Jews believe that G-d transmitted the oral Torah with the written Torah to Moshe on Mount Sinai. Each generation has passed down the oral Torah to the next generation until committed to writing, following the destruction of the Second Temple, in 70 CE, when the Jewish people faced dispersion from their homeland. Officially, Christians don’t accept the Oral Torah, which strikes me as unfortunate and myopic, because that limits their grasp of the message conveyed by the Torah itself. Jesus Himself would have learned the Oral Torah, being a Jew living during the Second Temple era. If it’s good for Jesus, then it’s good for me, too.

Anyway, to return to the matter at hand. In the Yoma tractates the Sages tell us about the fate of Azazel’s goat—the one charged with dispatching the goat ties a crimson thread to the goat and fastens it to a rock on the mountain of cliff, then pushes it off; the Israelites surmise that G-d has forgiven their sins when the crimson thread turns white. You can read Yoma 67a and 67b yourself. You can find all the Jewish texts on Sefaria.

So, to recap—in Leviticus Azazel’s goat stands (means not offered to G-d) to make expiation, it carries the sins of the Israelites, as a symbolic atonement. Azazel’s goat doesn’t get offered as a sin offering in the traditional way — it gets cast into the wilderness. Yoma 67a + 67b expands the discussion of the goat, giving a detailed description of the process for dispatching the goat over the mountain or the cliff, and providing a rationale for the argument that the Israelites push the goat off the cliff.

Question: What’s the purpose of Azazel’s goat? Answer: Atonement.

The Gospels of Matthew Mark and Luke

Artwork: Christ in the land of Gadarenes, by Jan Luyken, 1712, public domain

In the Gospel of Matthew, the demons have possessed two men. The demoniacs hung around the tombs, and no one could restrain them or go near them because of their extreme violence. The demoniacs feared Jesus, knowing His true identity as the Son of G-d, something people of that era didn’t fully grasp. The demons ask Jesus to cast them into a nearby herd of swine, which run off of the mountain side and plunge to their death in the body of water below. The herdsmen, seeing what happened, ran off to the town to report to the townspeople, who came out to meet Jesus and asked Him to leave the region.

The Markian telling of the story provides more detail about the demonaic. Mark tells the story of one demon-possessed man, not two. The man hung around the tombs, where he would cry out at night and cut himself with stones (like a self stoning). The townspeople had tried chaining him in the past, putting shackles and chains on his feet, and he had always broken free. Again the demons asked Jesus what He wanted, knowing who He was. Again, Jesus cast out the demons from the man, then asked the demons’ name. Legion asked to be cast into a nearby herd of swine, not wanting to leave the vicinity. The swine ran off the mountain side and plunged into the lake to their death. The herdsmen ran off to report what happened to the townspeople, who came to ask Jesus to leave. The townspeople saw the demonaic sitting at the feet of Jesus, fully dressed and behaving normally and it scared them. The man wanted to go with Jesus, who told him to stay and go tell his family the good news of what happened, and he did and they were amazed.

The Gospel of Luke tells a similar version of the Markian rendition, noting that the demonaic wore no clothes, and got driven to solitary places by the demons. The demon doesn’t drive the man to self harm with stones, as in Mark. Jesus asked the demons’ name—Legion they answered. Legion begged not to be cast into the abyss and asked to go into the nearby herd of swine. The swine ran off the steep embankment and plunged to their death in the water below. The herdsmen saw what happened, reported to the townspeople, who saw the demonaic dressed and acting normally, at the feet of Jesus. It scared the townspeople, who asked Jesus to leave. Jesus left, and as He left the man wanted to go with Him. Jesus told the man to stay and share the good news and so he did.

Comparative Analysis

In the Leviticus story of Azazel’s goat, and it’s Talmudic commentary, we see the crowd designating a victim to bear its collective sins, and then flinging that victim over the cliff or mountainside to make peace or atonement. We have a violent solution to the problem of perceived wrongdoing. We have a society that achieves atonement through violent destruction of the innocent. We have a society that tries to achieve peace through violent means. In the parable of Gadarene Demonaic, Jesus has turned that tradition on its head. Jesus has spared the designated scapegoat, the demon possessed man, and the herd of pigs has plunged itself over the mountainside to its death. Luke 17:33 comes to mind, as I write this, “whoever seeks to save his life will lose it, and whoever loses his life will preserve it.” Those who can choose to deny their selfish desires and egoistic self interest, in favour of serving others, those who engage and respond humbly rather than with arrogance and hostility—well, they will find lasting peace and true spiritual health.

Artwork: Job plagued by devils, by Lucas Vorsterman (I), after Peter Paul Rubens, 1619-1675, public domain.

In his book The Scapegoat, Rene Girard contrasts the memetic phenomenon of the mob flinging the designated wrong-doer from the cliff with the mob flinging itself from the cliff and the designated victim remaining safe and having his life spared. Girard writes as follows.

“But in these cases, it is not the scapegoat who goes over the cliff, neither is it a single victim nor a small number of victims, but a whole crowd of demons, two thousand swine possessed by demons. Normal relationships are reversed. The crowd should remain on top of the cliff and the victim fall over; instead, in this case, the crowd plunges and the victim is saved. The miracle of Gerasa1 reverses the universal schema of violence fundamental to all societies of the world,” (page 179).2

In his seminal work, Girard developed the scapegoat mechanism, based on his memetic theory. Girard noticed a competing rivalry playing out in literature, he surmised that it appears in literature because literature reflects human nature. Just watch children playing and observe how they eventually all want to play with the same toy. Or just observe the effect that marketing has on your cravings for things. We do learn about desire from others. That’s called memetic desire, when desire becomes a contagion. When we compete for that desired object, that’s called memetic rivalry. When we encounter an outsider or oddball in the throes of our memetic crisis, violence can and often does follow. So memetic desire, rivalry, violence all exist in society because it’s in our human nature to behave that way. Jesus came to teach us another way! He came to subvert the violent order of humanity, to teach us co-suffering and mercy.

In a discussion of Gerard’s work, theologian and scholar Bradley Jersak writes,

“when the mimetic rivals got rid of that person-perhaps they exiled them or threw them off a cliff-it was as if the scapegoat removed the sins from the camp and now everyone could be at peace. Granted, it was a pseudo-peace, a wicked fraud... but because the scapegoating mechanism diffused the violence and the scapegoat’s sacrifice brought reconciliation, ironically, the scapegoat (now dead) seemed sacred and somewhat godlike.”

Reader, when you examine mob violence, such as lynching, can you see the memetic mechanism at work? Can you see the wicked fraud perpetrated by lynching culture? Can you see the connection between the notion of a black sheep and scapegoating? When we speak of a black sheep, we often speak of a family context. A black sheep goes against the dysfunctional grain of the family, irritating and upsetting family members with her non-conformity. Non-conformity earns one the role of black sheep. Blame earns one the role of scapegoat. Ultimately, a similar memetic mechanism operates beneath the surface in each dynamic. I wrote about the memetic crisis about a week ago, in the context of cancel culture.

“Our instinct to blame is strong, and we target that blame into specific people or groups of people as a way to protect our own community. It’s especially strong when that blame is justifiable to everybody in your peer set, and singling out a particular person as being worthy of outrage can provoke a definitive wave of pile-on mimicry among your group.” — Alec Danco

Let’s return to the Gadarenes.

Gadarene refers to an area controlled by the Decapolis, a Hellenistic region, one distinct from Jewish regions. The herd of swine could serve as your clue for Gadarenes as gentiles. Therefore Jewish people of the time considered Gadarene a place of Other, where pagans and unclean people lived. The Gadarenes valued their livelihood (herd of swine) over human life (the Demonaic liberated from the demon possession and returned to peace of mind, health and life). On the verse Luke 8:32, Ephrem The Syrian comments, “the Gadarenes established a ruling for themselves that they would not come out or view the signs of our Lord. Consequently he drowned their swine so that they would have to come out against their will. “Legion,” which had been chastened, is a symbol of the world. He commanded the demons to enter the swine and not the man,” (Commentary on Tatiana’s Diatessaron, via Catena Bible). Girard draws a likeness between the herd of swine and the Gadarenes—swines embodying lapidation, a common practise of the time, and one in which Gadarene‘s engaged. Girard quotes Matthew 7:6, “… neither cast your pearls before swine, lest they trample them under their feet, and turn again and tear you,” (p. 182). Augustine of Hippo’s commentary on this verse notes that swine symbolise those who despise truth (via Catena Bible).

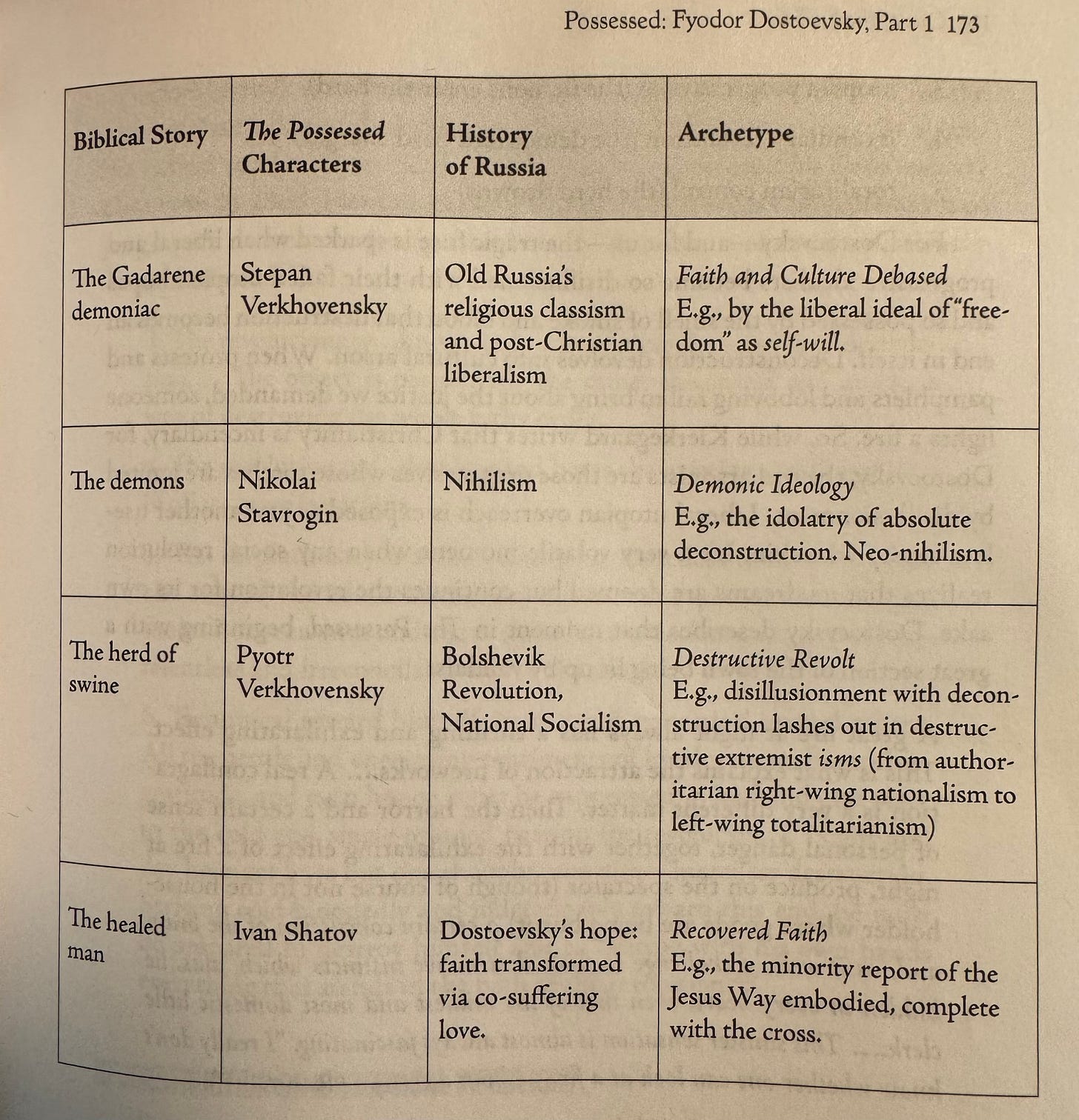

Finally, any discussion of the Gadarene Demonaic would not have completion without a mention of Dostoevsky. In the Augustinian vein, Dostoevsky saw the swine as symbolising a destructive revolt against a deconstructive force or process, “…disillusionment with deconstruction lashes out in destructive extremist isms (from authoritarian right-wing nationalism to left-wing totalitarianism),” (Jersak, p. 173)3

When we compare the stories of Azazel’s goat and the Gadarene demonaic, we can see a shift from using mimetic violence to achieve peace and atonement through destruction of an innocent victim whom the community agrees threatens its integrity and survival, toward a subversive event, in which Jesus defies the communal will, saving the victim and condemning the herd to death, thus destroying the livelihood of the community. We see a shift from the group achieving peace by condemning an innocent to the group facing condemnation so the innocent can achieve his peace. We see that Jesus has preserved one innocent man, one innocent soul, at the expense of a multitude of men and their swine herd.

Gerasa and Gadarene refer to the same location, where Jesus encountered the demoniac

René Girard, and Yvonne Freccero. The Scapegoat. 1986. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University. accessed via ProQuest Ebook Central.

Bradley Jersak. 2022. Out of the Embers: Faith After the Great Deconstruction. New Kensington, PA: Whitaker House.