Screeching and Bickering Like Baboons: the Cowichan Tribes Ruling

how does social media catalyse the mimetic crisis and the chaotic discourse that fuels populist movements?

I don’t have an answer to the question I’ve posed in the subtitle. I intended it more as a rhetorical question, one to grab you and get you thinking. I refuse to carry the projected guilt of the progressive left wing, aka Woko Haram, and I refuse to carry the projected fear of the Bannonist sect of the hardcore right wing.

illustration by Liana Finck via Luke Burgis

How much time do we spend on independent thinking? How much time do we spend, feeding on the desires of others which masquerade as thoughts? What impact do smart phones and social media platforms such as X have on our political discourse? Does it seduce us towards becoming idols of despair worship and away from becoming models of good behaviour?

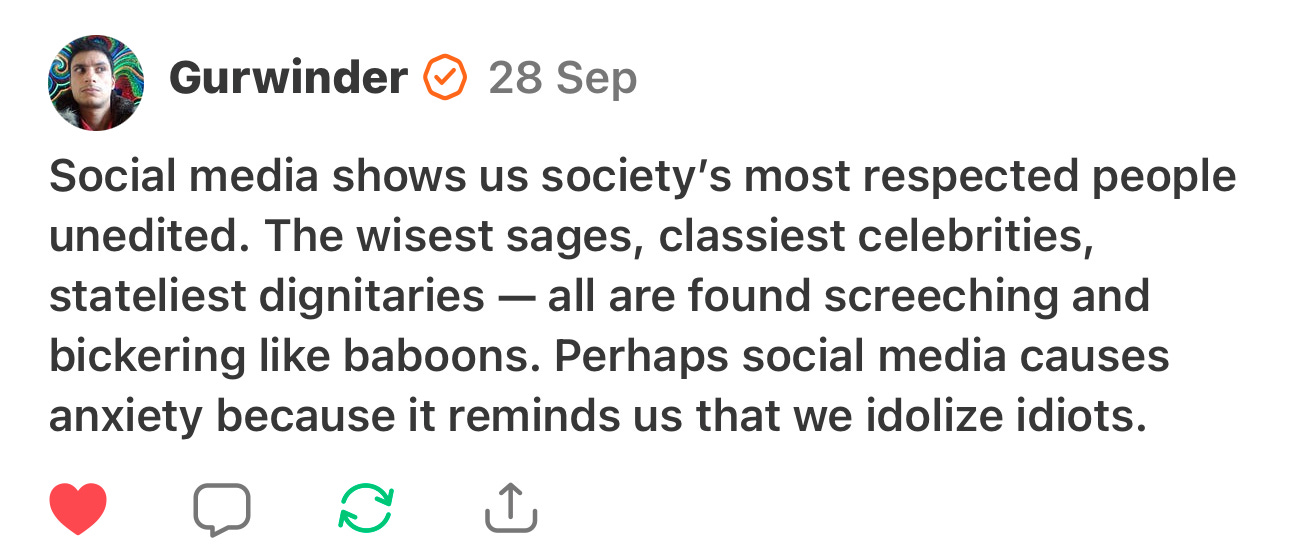

A sampling of the reaction to the Cowichan Tribes ruling

Reader, where does this demoralisation and bitterness come from? None of these lines of thinking add to our knowledge of the situation around the Cowichan Tribes ruling. In fact they obscure and misrepresent the factual reality. They obliterate the history. Whom does this serve?

Did the fear mongers and rage junkies read the parts of the ruling related to the intersection of Aboriginal land title and fee simple private property rights? Did they think about what it means? Did they contemplate the uncertainty they feel and the fear it creates for them? Did they meditate on their internal discomfort at the historical wrongs that live in the present? Did they make any efforts to come to terms with their unpleasant feelings about the ruling? Or did build an altar at the god they erected out their fears, making offerings of bitterness and anger to their fear idol, all with a view to soothing the discomfort and fear the Cowichan Tribes ruling creates for them, and all at the expense of the discourse?

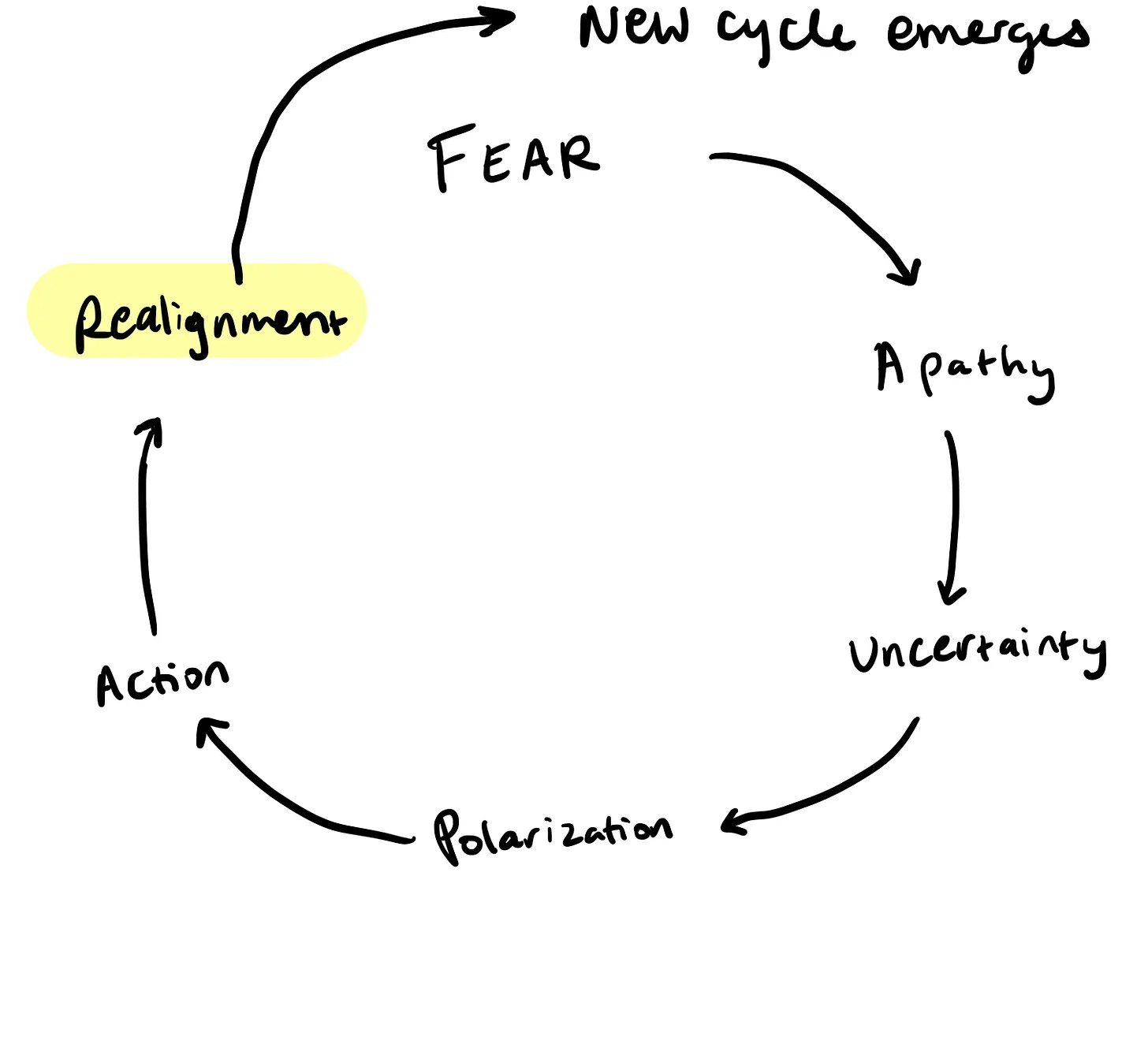

Reader, do you see how a mimetic crisis can draw people into a populist mindset and entice them into the psychology of warfare?

In the words of Chief Aaron Pete

“The idea that Aboriginal title might overlap with private property rights sounds terrifying.

Fear makes people irrational.

Fear is powerful. Fear makes people say things and vote for things they might later regret. That’s the danger. This ruling, while a legal victory for First Nations, could substantiate the idea that Canadians are settlers or unwelcome guests. That kind of framing risks turning reconciliation into an us versus them narrative.

First Nations on one side, ordinary Canadians on the other. That doesn’t build bridges, it builds divides. As a First Nations chief, I’m glad we’re moving beyond rhetoric and beyond empty land acknowledgements.”

“I don’t want to see our communities torn apart through this process. I hear the argument that we all Canadians, and I believe there’s truth to that. Yet, decisions like this can create distance.

And here’s the clarified metaphor. If that distance isn’t filled with honest dialogue, it will be filled with misinformation and fear. And once fear takes over, it’s like dropping chum in the water. Suddenly, everyone’s swimming in shark territory.”

“at the end of the day, reconciliation won’t be decided by judges and robes or politicians with microphones. It will be decided in classrooms, in workplaces, in city halls, and at kitchen tables. It will depend on whether we let fear define us or whether we build trust in its place.

It will be decided by whether we see one another as adversaries locked in a zero sum fight over land and history or as neighbors who share the same home. And that home is not just soil and property lines. It is the communities we’ve [built]…”

“legal clarity is not enough. If First Nation leaders don’t step forward to explain what this means, not just for us, but for everyone, then other voices will define it for us. And those voices will not build bridges. We need to hold two truths at once. One, the Aboriginal title exists and that it matters. And two, Canada only works if everyone, indigenous and non-indigenous, feels like they belong here together. If we lose sight of either truth, reconciliation collapses into either empty symbolism or bitter division.”

“And here’s the thing, Aboriginal title is real. It didn’t vanish when cities rose, when treaties failed, or when crown grants tried to bury it in paperwork. For 150 years, indigenous peoples carried that truth. And now the courts have acknowledged it. But Canadians also live another truth. We need stability. And right now, that stability is fragile.”

A historical timeline of Indigenous land rights

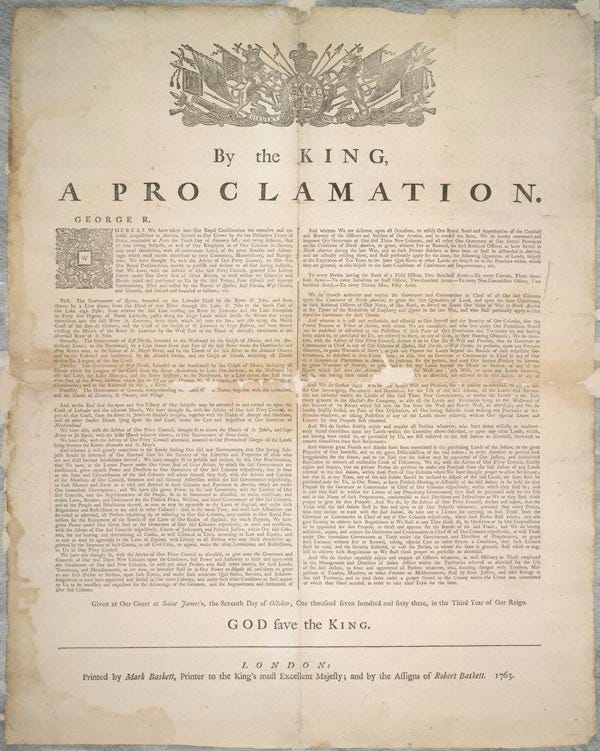

The Royal Proclamation of 1763 acknowledged Indigenous1 title on all lands not ceded by or purchased from Indigenous peoples, and said that no colonial governors may make any land grants from Indigenous land.

Section 24(91) of Constitution Act of 1867 grants the parliament of Canada the power to create laws and make policy regarding Indigenous peoples.

The Constitution Act of 1982 states in Section 35(1) that “…the existing aboriginal and treaty rights of the aboriginal peoples of Canada are hereby recognized and affirmed,” and in Section 35(3) that “…for greater certainty, in subsection (1) treaty rights includes rights that now exist by way of land claims agreements or may be so acquired.”

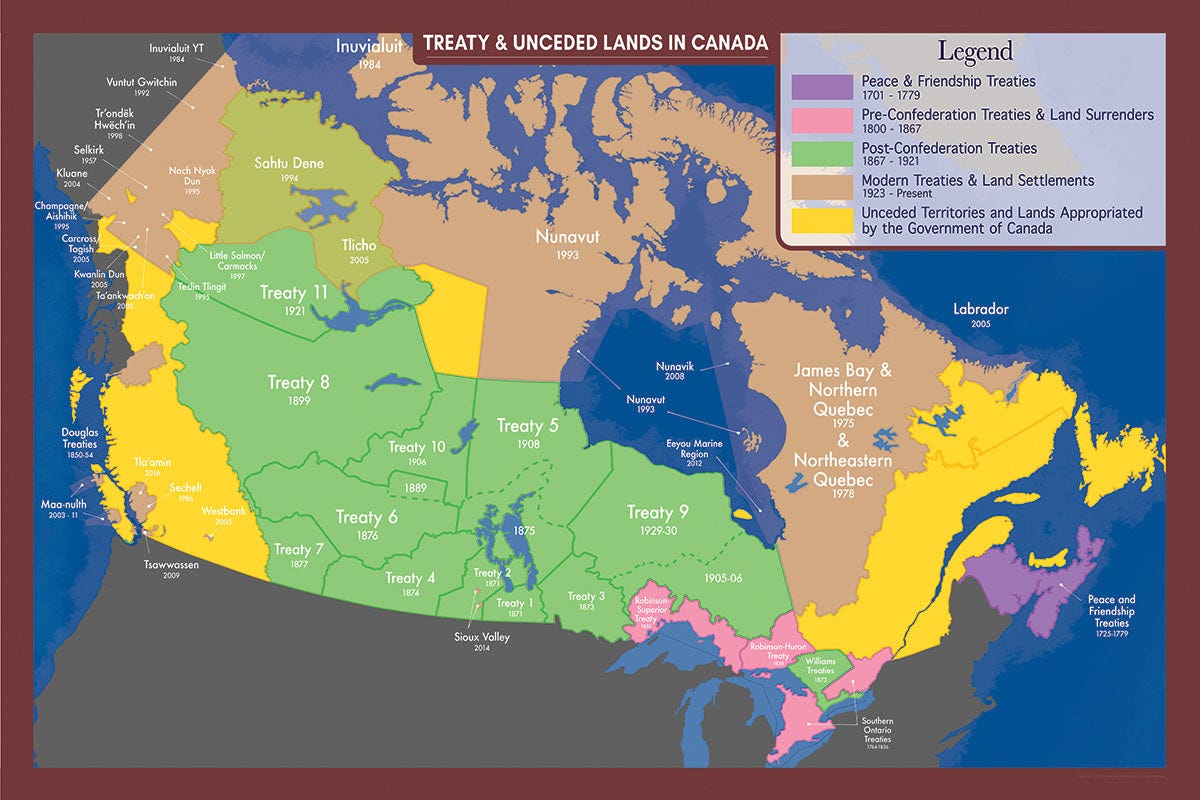

Map of Treaty and Unceded Territories in Canada via Indigenous Reflections

Aboriginal land claims: a BC case history

The Calder ruling recognised Aboriginal title in Canadian law and influenced the inclusion of Section 35 in the 1982 Constitution, as well as setting a precedent for future land claim cases. Though the Nisga’a lost the case, the ruling did lead the federal government to implement a comprehensive land claim policy, and it forced the hand of the B.C. government to negotiate with the Nisga’a, who achieved self-government in 2000. The Nisga’a treaty became the first modern-day treaty in BC and served as an important step for First Nations seeking to establish treaties with the Crown, and self-government for themselves.

The Sparrow ruling established a set of criteria to interpret Section 35 of the 1982 Constitution, in determining what constitutes an Indigenous right, since Section 35 doesn’t provide specifics. the ruling granted Ronald Sparrow the right to fish as an ancestral right.

The Van der Peet ruling defined and restricted the scope of Aboriginal title, creating the Van der Peet test, “to prove an Indigenous right. To constitute an Aboriginal right, an activity must be an element of a custom, practice or tradition forming an integral part of a distinct culture of the Aboriginal group that claims the right in question.” The Van der Peet criteria narrowed those established by the Sparrow ruling. Dorothy Van der Peet lost her case, in which she claimed as an ancestral right the right to sell to a non Indigenous person salmon she caught under a food and ceremonial license.

The Delgamuukw ruling clarified the content and definition of Aboriginal title. The SCC determined that the provincial government did not have the authority to extinguish Gitxsan and Wet’suwet’en title, ruling that Aboriginal title existed as an ancestral right derived from Section 35 of the 1982 Constitution. It affirmed that the Crown must consult with Indigenous people regarding land use, and it affirmed the legal validity of oral history, which had a primary role in the Cowichan Tribes case. It set the stage for the Tsilhqot’in ruling. The Delgamuukw ruling established a test of proof for Aboriginal title: “…sufficient, continuous and exclusive evidence of territorial occupation.”

The Tsilhqot’in ruling emerged from the Tsilhqot’in Nation’s desire for right of refusal of logging activities on its traditional territory. The case granted Aboriginal title to the Tsilhqot’in, affirming that the province has no authority to extinguish Aboriginal title, and that the Crown’s decision to develop the resources of Aboriginal land does not extinguish an Indigenous peoples claim to its ancestral land.

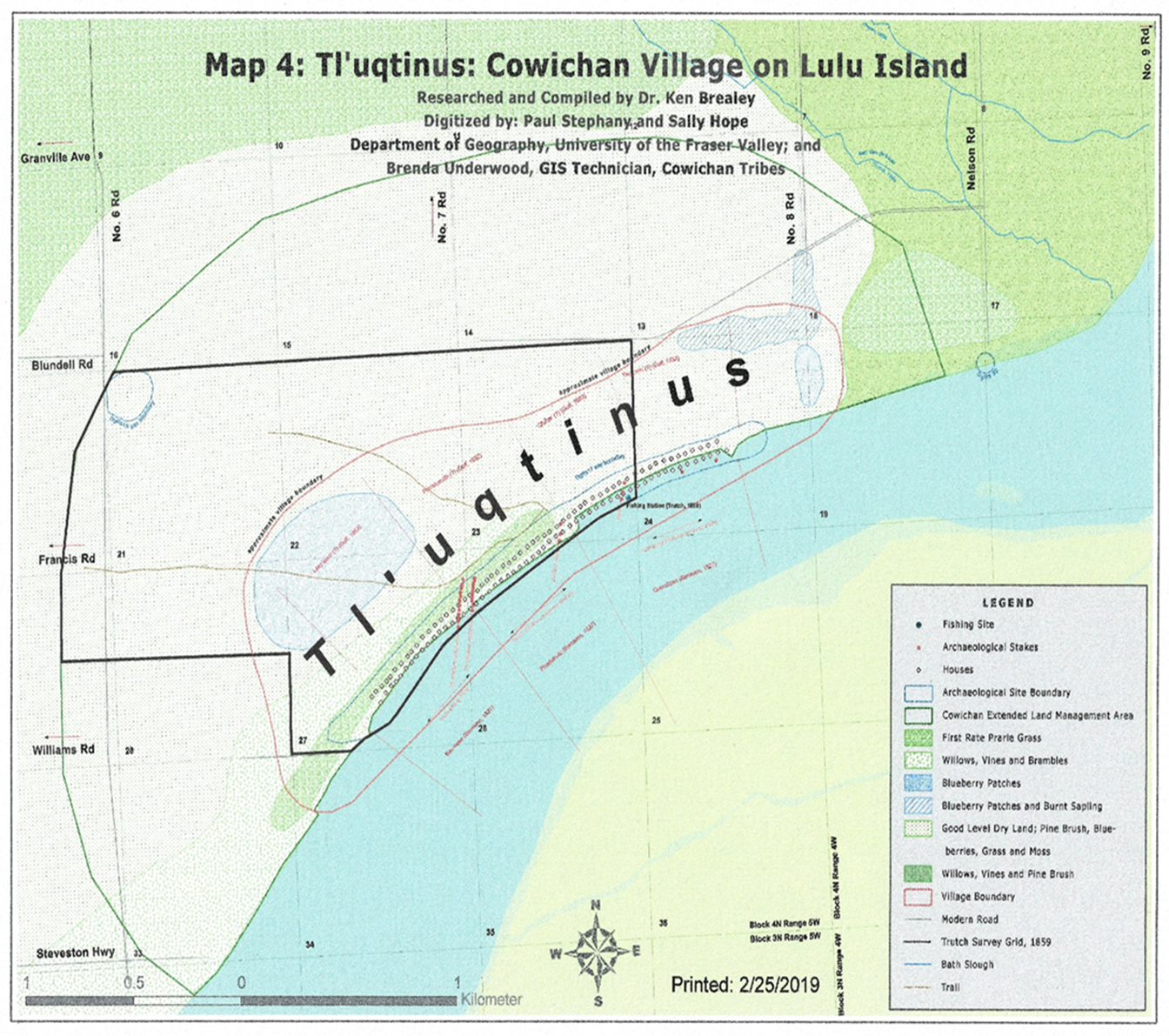

The Cowichan Tribes ruling granted Aboriginal title of the Lands of Tl’uqtinus to the Cowichan Tribes. Lands of Tl’uqtinus refers to a 7.5 square kilometre tract of land in present day Richmond, where a shipping terminal and a fuel depot now sit. This 7.5 square kilometre tract of land, on the south arm of the Fraser River, was the site of an ancestral Cowichan fishing village. The ruling affirmed that the provincial government cannot extinguish Aboriginal land title.

Sometime after his appointment in 1858 as a Crown-appointed land commissioner responsible for setting aside land reserves for Indigenous peoples, Richard Moody secretly sold himself (as a speculator) some of the land reserved for Indigenous peoples. The federal Crown, the B.C. government, the Vancouver Fraser Port Authority, the City of Richmond and private third parties each have title on the disputed land.

The Cowichan Tribes ruling designated the Crown and City of Richmond land titles within the 7.5 kilometre tract of land defective and invalid, and the judge suspended her ruling for 18 months to allow for negotiations to take place to reconcile Aboriginal title and fee simple interests (ie private property). Both Tsawwassen and Musqueam Nations opposed the Cowichan Tribes’ claim to Lands of Tl’uqtinus. The ruling did not extinguish the property title of homeowners living in the tract of land.

“Today, over 780 acres of the Cowichan Nation settlement are owned by the government of Canada, its agent the Vancouver Fraser Port Authority, and the City of Richmond. The Cowichan Nation is seeking to recover those publicly held lands – much of which remain undeveloped. The Cowichan Nation is not seeking to recover any privately held lands in the court case. For these lands it is seeking a negotiated reconciliation with government.” — Cowichan Tribes, 2024

I see a lot of ego defense mechanisms at play in the discourse related to the Cowichan ruling. I see projected anger and fear, I see scapegoating of Indigenous people and I see inflammatory and mean spirited responses.

I get that, it deeply resonates with me because this reaction mirrors the bitterness and hurt that emerged in response to the mass graves hoax and the ongoing Woko Haram narrative that Canadians are uninvited guests in the land of their birth, or the land onto/into which they’ve become naturalised. I myself have strong feelings and opinions about these issues and they caused me to publicly reject any truth and reconciliation process because TRC felt like a cudgel not a resolution to the crisis or a reasonable way forward. I refuse to take responsibility for things I didn’t do. I refuse to accept responsibility for the awful things that sh1tty men said and did hundreds of years before I became even I gleam in my daddy’s eye. That’s simply abusive to project that onto Canadians, it harms any chance of Canadians coming to terms with our painful history. I do accept responsibility for the BC government’s modern day refusal to engage in good faith treaty negotiations with First Nations, to settle outstanding land claims.

BC Treaty Commission Negotiation Updates

I can still acknowledge the reality of outstanding Aboriginal land claims in parts of Canada whilst rejecting the mass graves hysteria, the desire to criminalise skepticism of the mass grave hysteria, the uninvited guest label, and the bigoted pretense of the noble savage victimhood cult. In fact, I think we need to drop the Woko Haram radical noble savage victimhood cult of projected guilt when it comes to engaging the TRC process. The Woko Haram approach to rectification of a painful history embodies an ethic that goes against reconciliation. It tokenises Indigenous peoples and removes their agency—suppresses the self responsibility they need to cultivate resilience that will help them climb out of learned helplessness that colonialism drove into their cultural ethic and identity. If we do not dismantle the Woko Haram framework, as Chief Aaron Pete says, the TRC process will devolve into a bitter zero sum game over a fight for land and history. I wonder how much the Woko Haram and Bannonists mirror and fuel each other. I wonder whether these ideological sects embody the same toxic ethic embedded in each their particular side of the political spectrum.

As an aside, fee simple estate sits on top of Crown title. When you buy property, you sign a contract, receive a title, and you pay a lease to the Crown in the form of property taxes. You can have no mortgage and you’re still on the hook for property taxes. The Cowichan Tribes ruling means that Crown title of disputed territory has a burden of Aboriginal title. Look at the map of Canada, the yellow area denotes territory with no treaties governing them. Starting with Joseph Trutch’s generation of Crown appointees, the B.C. government sat around fc*king the dog and dodging denying its responsibility to settle the land claims.

“The Indians have really no rights to the lands they claim, nor are they of any actual value or utility to them; and I cannot see why they should retain these lands to the prejudice of the general interests of the Colony, or be allowed to make a market of them either to Government or to individuals.” — Joseph Trutch via Law Lessons

Joseph Trutch served as a Land Commissioner and then Lieutenant-Governor for B.C. Trutch espoused a strong hatred for Indigenous people and did everything he could to sever their attachment to their ancestral lands.

Through the Cowichan Tribes ruling, the court forced the hand of the B.C. government to settle outstanding land claims. Welcome to reality. There’s little to dispute, it’s fairly clear, and the court has reiterated that clarity several times over. We are here now: be here now. We would do well to stop the hysteria and chaos-making and get on with the business at hand, that being reconciliation and working towards national unity.

I see the same people, self identified Christians—who banged on about Christian persecution as they carried banner for the Christian nationalist American preacher Sean Feucht—now bitterly whinging about First Nations land grabs or land heists. Wow. Look, dude, you can’t steal what always belonged to you. It’s funny because these self identifying Christians support Eretz Yisrael, meaning they support the Jewish claim to lands of the ancient Kingdom of Israel.2 The self-identifying Christians see the Arabs as conquestors and colonisers, they frequently express disdain at the Islamic appropriation of the Temple Mount and of also of the Hagia Sophia. Yet, they don’t see the same things in their own homeland of Canada.3 Why’s that?

I have no answer for that painful question. I ask these questions to provoke readers to think about this stuff. When you look at history with a critical eye, we all have blood on our hands, victims can also victimise. Maybe that’s the lens we must look through when we come to the reconciliation table.

To the Christians who have waged a rhetorical war with their words on social media, using phrases like land grab or land heist — do you think that’s what your faith ethic calls you to do? Do you think these kinds of accusations align with The Jesus Way? That’s for you to answer, this isn’t a sermon, it’s an essay to hopefully motivate you to engage a self examination process and critically think for yourself about these issues, your ethical + moral + political position on them, and the way forward for you + your children + your community + your country.

Freaking out, rage-baiting, and political theatrics don’t address the issue. These responses drive us further away from our objective — truthful reconciliation and national unity. We must begin engaging in meaningful ways. We must recognise the mimetic forces at play in the discourse, and we must work to break their gravitational pull on our psyches.

image via Kyla Scanlon, Trust as the Next Great Commodity

Your kids are watching; your grandkids are watching. What lessons will you teach them? What legacy will you leave them?

Note that I use Indigenous and Aboriginal interchangeably in this essay.

One could see the more nuanced perspective in the Israeli story, that being many pro Israel people cannot reconcile the appropriation of Arab homes and property that happened after the Arab leaders told their people to flee the area and leave their homes and property. It’s difficult to hold these two truths, that Jews have an ancestral attachment to the land, and that some Arabs (whom we call Palestinian in modern times) also do, too.

We could go deeper into the story of historical wrongs and have a conversation about the historical wrongdoing of Indigenous people — their own slavery practises, the fact that a demand for rum created a demand for slave and indentured labour to power the plantocracy in order to fill the demand for sugar.

<< Look at the map of Canada, the yellow area denotes no territory with no treaties governing them. >> I think you want to delete the first "no" in this sentence.