Perseus and Moshe

Comparing Archetypes Across Mythology

1 :: Mythos means story, what if it really means the human story?

Aficionados of Joseph Campbell will have familiarity with his discourse on archetypes in religious and cultural mythology. They’ll know that George Lucas drew inspiration from the Hero’s Journey motif in his Star Wars world building and to create the stories it inspired that we know and love today as part of our popular culture. Anyone familiar with Greek mythology might find familiar themes in the mythology of the Hebrew Bible aka Old Testament. Anyone familiar with myth from across a few cultures will know that myth tells the story of the human condition. They will have learned that culture informs myths to a great degree, and yet across the board, when distilled down to their elements, the stories have fundamental similarities.

As I recover from my broken ankle and await my surgery1, I’ve had the opportunity to watch Great Greek Myths on Amazon Prime. Having watched the story of Perseus retold in the Amazon Prime series and having watched Clash of the Titans a few times, and having read and studied the story of Moshe in the Torah, and seen the Charlton Heston movie many times, I see an archetype when I compare the stories of these two mythological heroes.

“While outlining the basic stages of this mythic cycle, Campbell explores common variations in the hero's journey, which he observes is an operative metaphor not only for an individual, but for a culture as well.” — Joseph Campbell Foundation

2 :: How do the myths of Perseus and Moshe compare?

Both heroes began life being placed into a container and put in a body of water due to a King’s fear of a defeat.

In the story of Perseus, King Acrisius of Argos fear the prophecy of the Oracle at Delphi, who told him his grandson would kill him. As a result Acrisius locked his daughter Danaë in a bronze tower, which Zeus infiltrated by taking the form of golden rain, and seduced the princess. After the birth of Perseus, Acrisius placed mother and babe into a wooden chest and threw them into sea.

In the story of Moshe, the Pharaoh declared a moratorium on all Hebrew male births, ordering any males born thrown into the Nile River. Jochabed gave birth to Moshe in defiance of the royal edict and kept him for as long as she could, then eventually chose to place him in a reed basket and allow Miriam to place him in the Nile, where the Pharoah’s daughter found him. In each myth, we see our respective hero found in a container plucked from a body of water by the one who will raise him.

A simple fisherman raised Perseus, the son of the god Zeus. The daughter of the Egyptian Pharaoh2 raised Moshe, the son of Hebrew slaves. In this life detail the two heroes seem like a chiasmus.

Born in a royal court and hidden by his mother from his grandfather the king until being cast into the sea, Perseus grew up a fisherman’s son, and went beyond Oceanus, (the outer ocean) to Island of Sarpedon on a quest to kill Medusa. Afterwards he lived a Greek warrior life. Perseus inherited the kingship of his grandfather’s dynasty, which he traded with another king, and he came to lead the people of Tiryns. Perseus slayed many monstrous creatures, including the Gorgon, to save his mother. Perseus killed Cetus the sea monster to save Andromeda. He turned several of his foes to stone with the head of Medusa.

Born in a slave community and hidden by his mother from the king until being placed in the Nile River, Moshe grew up in a royal court, until he fled the Egyptian court and became a shepherd. After seeing the burning bush on a Mount Horeb, Moshe lived the life of a Hebrew patriarch who led his people out of slavery. Moshe parted the Sea of Reeds so his people could escape the Pharaoh’s army. Moshe did lead battles against the Amalekites and Medianites.

When Perseus decapitated Medusa, Pegasus the (winged horse) flew out from her. When Moshe accepted the call from G-d the burning bush, he receives the unpronounceable name of G-d, which we call the Tetragrammaton.

Both Perseus and Moshe received Divine help to overcome formidable enemies and to complete challenging feats. Perseus slays formidable monsters to prove his worth to powerful men and even gods, whereas Moshe performs formidable miracles that inflict plagues upon the Egyptians, in an effort to convince the Pharaoh to release the Israelites. Both men lived a hero’s journey life in which they fulfilled a quest for a boon.

It’s said that Perseus’s son Perses begat the Persian people. In the Myth of Moshe, it’s said that Moshe founded the Judaic religious tradition.

3 :: Does monomyth underscore our human connection to each other?

In my research on the comparison between the Greek mythology and Torah mythology, scholarly and historical sources indicate Greek mythology predates Torah mythology. If Moses existed as a historical figure in 13 BCE and he wrote the Torah, then he predates the written Greek myth of Perseus, dated 8 BCE. It’s always possible that the oral stories of Perseus existed long before they appeared in writing. If Moses didn’t exist as a historical person, then it’s probable that the written Greek myths predate the Torah.

So, Judeo Christian belief says Moshe lived around 13 BCE, and no archeological and historical evidence to support that claim. Incidentally no evidence exists to prove the Exodus happened. Nonetheless, as Jews and Christians, we receive the instruction to believe without proof. That’s faith, they told me as a child. When did the Torah get written? Before or after the Greek myths? That’s a question I can’t answer here, yet.

Anyway.

It all leads me back to (the Catholic) Joseph Campbell’s work and the study of myth as an expression of our collective unconscious. Myth helps us understand the human condition. Myth reminds us that humans have more in common and more connections that we might realise.

“This is what [James] Joyce called the monomyth: an archetypal story that springs from the collective unconscious. Its motifs can appear not only in myth and literature, but, if you are sensitive to it, in the working out of the plot of your own life. The basic story of the hero journey involves giving up where you are, going into the realm of adventure, coming to some kind of symbolically rendered realization, and then returning to the field of normal life.” — from Pathways to Bliss via JCF

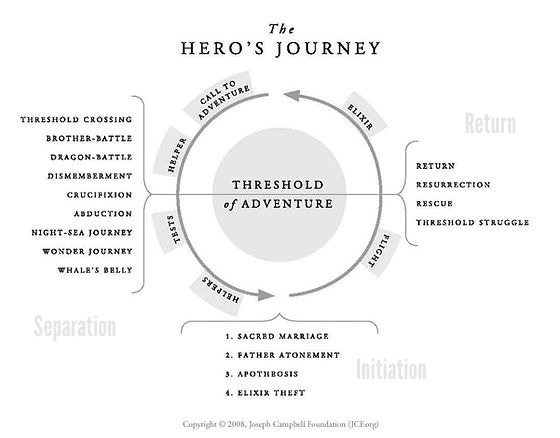

If we apply the Joseph Campbell Monomyth3 paradigm of Separation-Initiation-Return to the stories of Perseus and Moshe, we can see the parallels in the stories. Contrary to popular belief, not every myth or story will have each step. Campbell envisioned these steps as a guide more than a rigid framework.

However, Campbell did envision four possible adventure climaxes: the Sacred Marriage, Atonement with the Father, Apotheosis, or the Elixir Theft. Sacred Marriage denotes a union that enables transcendence, Apotheosis denotes elevation to a high status, it denotes culmination, and Elixir Thief denotes a situation where the hero retrieves something like a treasure or a special power from the antagonist, in order to complete the quest. Atonement with the Father seems self evident, it denotes coming to terms with a power-holding paternal figure that’s dominated their life or governed their origin story.

In the story of Moshe, as with most of Judeo-Christian mythos, Atonement with the Father figures prominently. One could argue for a measure of Apotheosis in the myth of Moshe. In the story of Perseus, Atonement with the Father also features prominently. One could also argue for Sacred Marriage, and a variant of Elixir Thief.

4 :: What if we miss the point when we need myths to be true?

We could argue whether or not a bloke named Moshe existed and wrote the Torah. Some people live by that mindset. Whatever floats your boat, reader. We can expend put intellectual energy proving the historical accuracy of the cultural myths that guide us or we can study them for what they can teach us about how to hooman better in our relationship and life endeavours. It depends if you want to be right or be in the light, doesn’t it?

When we study Greek mythology, we don’t spend much time or energy on whether or not these heroes in the myths really existed. We study the story by applying literary analysis, and we study cultural and ethical themes in the myths. The word myth has its etymological origin in the Greek word for speech or story or narrative. That’s in contrast to the word history, which has its etymological origins in the Greek word for knowledge or inquiry or account.

5 :: Why do we cleave to myth?

Personally, I think it more important to study the themes in the myth of Moshe, to apply a literary analysis technique to our study of the myth of Moshe. Doesn’t matter if he was real? I don’t think it does.

The strength of the Jewish tradition lies in the literary analysis of the Torah in the weekly study of the Torah Parsha. My Catholic upbringing focused more on rituals and the doctrine and sacraments than on the literary richness of the Bible. This year I decided to follow the Torah cycle. Following this weekly reading cycle, entails reading the Torah portion for that week and then studying the narrative elements, ethical elements, and thematic patterns present in the portion. Throughout the Torah you can find interconnected themes, particularly when you consult the Hebrew primary source text in your Parsha study.

Ultimately we rely on myth to carry us through the stages of our lives, as individuals and in the collectives to which we belong. As historical and social beings on a quest, myth and story play an integral part of our seeking and orientation. Humans are stories and we exist in larger stories, in consecutive fashion. Like a matryoshka doll, we are really stories nested inside other stories.

Art work used in this essay :: Danaë, JW Waterhouse, 1892 | Moses saved from the waters, Orazio Gentileschi, Prado, 1633 | Matryoshka Dolls, Fanhong, 2005 via Wikipedia

I’m in a day surgery queue as of September 17th, and get called each morning as to whether they can fit me the daily surgery slate.

In Egyptian culture Pharaoh served as a kind of dynastic god.

In the words of Joyce and Campbell, Monomyth “refers to an archetypal story that originates from the collective unconscious.” Monomyth encapsulates the phenomenon of archetypal stories existing in literature and folklore across cultures. Joyce first coined the phrase, in conjunction with Finnegan’s Wake, in which he tried to write a story that exhibits the cyclical nature of the narrative of human life and development.