A Critical Analysis of Hannah Arendt’s Forgiveness

Does Forgiveness Have Limits? Does Love Guide Forgiveness?

Hello readers. I wrote a paper on Hannah Arendt’s conception of forgiveness for one of my theology grad study courses this past semester. I thought I would share it here. My word limit was 1000 words. I scored an A for this paper.

“For me, forgiveness and compassion are always linked: how do we hold people accountable for wrongdoing and yet at the same time remain in touch with their humanity enough to believe in their capacity to be transformed?”

—Bell Hooks, in conversation with Maya Angelou

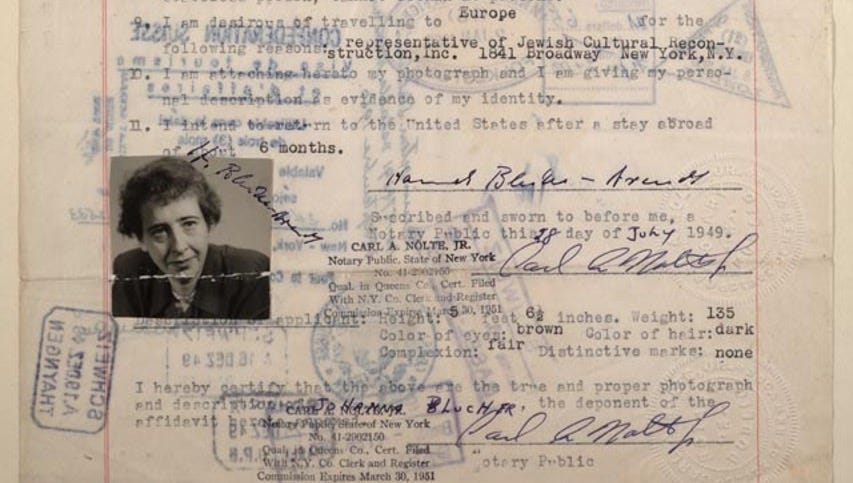

image: Portion of “Affidavit of identity in lieu of passport” in which is written, “I wish to use this document in lieu of a passport which I, a stateless person, cannot obtain at present.” The Hannah Arendt Papers (Library of Congress, Manuscript Division).

Arendt credits Jesus with discovering human forgiveness. However, the concept of forgiveness which Arendt wrote about in The Human Condition differs vastly from the forgiveness that Jesus taught and preached during His ministry. For Arendt forgiveness has a limit and it has its root in merit and mutuality. For Jesus, forgiveness exists as a limitless and radical embodiment of mercy. One never deserves forgiveness, one receives it as a grace from the victim.

Jesus taught and preached radical forgiveness. In his lecture The Life of the Church in a Secular Age, Charles Taylor explains how, through kenosis, Jesus had the ability to see people. He didn’t have to wrestle with the barnacle-clad perception that humans have to do, when relating to others. Jesus instructed His disciples to forgive seventy times seven, meaning as many times as it takes. G-d forgives us as we forgive our trespassers. We are never worthy of the mercy of G-d, and we must follow Jesus and extend mercy to those whom we do not consider worthy. He taught that, when we refuse to forgive, we fall into the harmful cycle of wrath and vengeance which our rejection of mercy creates. Jesus warned that G-d will judge us as we judge others.

Jesus modelled the opposite of what Thomas Merton described in No Man is an Island. “We see things as they are not, because we see them centered on ourselves. Fear, anxiety, greed, ambition and our hopeless need for pleasure all distort the image of reality that is reflected in our minds. Grace does not completely correct this distortion all at once: but it gives us a means of recognizing and allowing for it.”1 Does grace give us the vision to recognise ourselves in the offenses of others, and does this enable us to forgive what, at the outset, might seem unforgivable? I think after the Eichmann trial that Arendt saw this in her own way.

In her book The Human Condition, Arendt, saw forgiveness as breaking the chain of violent reaction to a past harm, mitigating the harm of an irreversible reaction. Arendt goes as far as to say that “forgiving …serves to undo the deeds of the past.”2

I think that’s untrue, and after the Eichmann trial she somewhat changed her thinking. Forgiveness cannot erase or undo an offense, it can only liberate the victim from the bondage of a human desire for vengeance, ie. to settle the score. Forgiveness requires us to remember the offense, to forgive means to move past the harm done, in such a way that it no longer governs your heart.

“Once initiated, forgiveness becomes a continuous and internal act.”

We forgive the person, not the offense. The forgiver engages forgiveness for herself. In doing so, she begins the chipping away at the sclerosis blocking the relationship connection with the offender. Once initiated, forgiveness becomes a continuous and internal act. Forgiveness serves as a reaction that potentiates a new and novel action. Pre-Eichmann trial Arendt would disagree with me—for her forgiveness has a basis in merit, it requires plurality, otherwise it lacks depth. In The Human Condition, Arendt limits the application of forgiveness to unintentional harm, and to situations where the offender expresses contrition.

For Arendt, individuals who commit radical evil and extreme crime cannot receive forgiveness. What does this mean for our identity when we refuse to forgive radical evil or extreme crime? We see our self in relation to those elements in our surroundings, our culture, and our experiences which matter to us.

What self identity have we cultivated when we choose to cleave to the very worst things others have done? What does it say about the legacy we’ve inherited when we have drawn into our identity the radical or willful evil acts which another has committed, and define that other by these acts? Does it say something about our own self identity when we identity others solely by the worst things they’ve ever done? Is forgiveness an endowment of our own identity?

Arendt dismisses the need for divine power in her conceptualisation of forgiveness, as she dismissed the need for love to guide forgiveness. To forgive a person simply for who they are would mean that we must forgive him no matter what he’s done. For Arendt this takes forgiveness beyond the realm of human consideration and possibility.

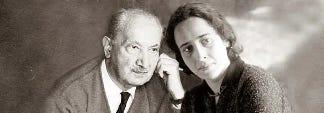

Interestingly, Arendt did forgive Heidegger for the radical evil of joining the Nazi party and remaining unrepentant in his extreme antisemitism. Arendt forgave him out of love, based upon who he was to her as a human. She reasoned that Heidegger’s Nazi interlude didn’t make Heidegger a monster. Rather, it made him a flawed individual. Rosenthal believes Arendt unreasonable in her forgiveness of Heidegger. Perhaps so. Doesn’t love defy reasonability? Maybe forgiveness borne out of love seems unreasonable to the onlooker.

“We mustn’t think that we would not be an Eichmann of our own age.”

Did Arendt create an “exculpatory doctrine of evil?”3 Rosenthal thinks so. Like many other Jewish thinkers, Rosenthal heavily criticises Arendt for her framing of evil as banal. During the Eichmann trial Arendt came to realise the banality of evil. We like to imagine the perpetrators of radical evil as far removed monstrous creatures. Does it humble us to see the similarity between evil doers and ourselves? There but for the grace of G-d goes I, says the old adage.

The horror of evil embodied in Eichmann lay in his ordinariness. We mustn’t think that we would not be an Eichmann of our own age. Throughout his trial, Eichmann revealed himself a mundane and amoral creature. Operating within the Nazi machinery, he failed to use his powers of discernment, if he had any, and he never intended, much less calculated the harm that would ensue from his participation in organising the Holocaust. Nonetheless, Arendt could not consider the extension of forgiveness to Eichmann. Yet she had forgiven Heidegger. It would seem love does play an important role in our capacity to forgive the seemingly unforgivable.

References

Adrian Horton. “A Life in Quotes: Bell Hooks.” The Guardian, December 15, 2021. https://www.theguardian.com/books/2021/dec/15/bell-hooks-best-quotes-feminism-race.

Amor Mundi. “Forgiveness.” Hannah Arendt Center for Politics and Humanity Bard, March 25, 2013. https://hac.bard.edu/amor-mundi/forgiveness-2013-03-25.

Christopher F. Koop. “The Politics of Christian Forgiveness: An Augustinian Assessment of Hannah Arendt.” McMaster University, 2015. https://macsphere.mcmaster.ca/bitstream/11375/18347/2/Koop_Christopher_F._2015October_Ph.D..pdf.

Daniel Maier-Katkin and Birgit Maier-Katkin. “At the Heart of Darkness: Crimes against Humanity and the Banality of Evil.” Human Rights Quarterly 26, no. 3 (2004): 584–604.

Daniel Maier-Katkin and Birgit Maier-Katkin. “Hannah Arendt and Martin Heidegger: Calumny and the Politics of Reconciliation.” Human Rights Quarterly 28, no. 1 (2006): 86–119.

Hannah Arendt. “Eichmann in Jerusalem I.” The New Yorker, February 9, 1963. https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/1963/02/16/eichmann-in-jerusalem-i.

Hannah Arendt. Eichmann in Jerusalem: The Report of the Banality of Evil. The Viking Press, 1964.

Hannah Arendt. The Human Condition. Edited by Margaret Canovan. University of Chicago, 1998.

La Caze, Marguerite. “Should Radical Evil Be Forgiven?” In Forensic Psychiatry, edited by Tom Mason. Humana Press, 2006. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-59745-006-5_14.

Laurens van Esch, “Final Pre-recorded Lecture on Taylor and Arendt and Identity,” CUL/PHIL 5270: In Quest of “the Good” - Charles Taylor & Hannah Arendt online lecture at St. Stephen’s University, St. Stephen, NB, November 17, 2025

Lee, Shinkyu. “The Political vs . the Theological: The Scope of Secularity in Arendtian Forgiveness.” Journal of Religious Ethics 50, no. 4 (2022): 670–95. https://doi.org/10.1111/jore.12414.

Mike Cosper and Frank Bruni. “Humility in the Age of Cancel Culture.” Christianity Today, October 2024. https://www.christianitytoday.com/2024/09/humility-cancel-culture-frank-bruni-mike-cosper/.

Rosenthal, Abigail L. “Defining Evil Away: Arendt’s Forgiveness.” Philosophy 86, no. 2 (2011): 155–74. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0031819111000015.

The Life of the Church in a Secular Age. Performed by Charles Taylor. The Life of the Church in A Secular Age. The Conférence Mondiale des Institutions Universitaires Catholiques de Philosophie, 2015. 33:31.

Thomas Merton. No Man Is an Island. Rare Treasures, 1955.

Wonicki, Rafał. “Between the Ethics of Forgiveness and the Unforgivable: Reflections on Arendt’s Idea of Reconciliation in Politics.” Argument: Biannual Philosophical Journal 10, no. 1 (2020): 27–40. https://doi.org/10.24917/20841043.10.1.2.

Merton 1955, p. 173

Arendt 1998, p. 237

Rosenthal 2011, p. 155