Shake the Dust off Your Feet

when exile becomes a vocation

Matthew 10:14

“And if a home or town refuses to welcome you or listen to you, then leave that place. Shake its dust off your feet.” (International Children’s Bible)

“Sometimes you will go to some house or town and the people will not accept you there. They will not listen to your message. Then you should leave. Clean the dirt of that place off your feet.” (Disciples’ Literal New Testament)

“And if anyone will not receive you or listen to your words, shake off the dust from your feet when you leave that house or town.” (English Standard Version)

Reader, I have recently finished reading the Gospel of Matthew in its entirety. A few things stood out for me, however one passage in particular resonates loudly and clearly for me these days. It’s the passage where Jesus tells His apostles to shake the dust off your feet. You can find this verse in line 14 of chapter 10. Essentially it says that, if you go somewhere and try to speak with and engage people and they reject you, then you must leave that place and shake the dust off your feet.

The shaking of dust off one’s feet relates to an ancient custom in Judea, when Jews would shake the dust from their feet after visiting a Gentile place and before reentering a Jewish place. It’s an act that symbolises separation from an unclean or impure or unworthy place. It’s a concrete way that we can say to those who abuse or reject or debase us, look, muppet your horsesh1t belongs to you, watch me dust off your dirty attitude from my self and move on and live my best life.

I’m reading Out of the Embers: Faith After the Great Deconstruction by Bradley Jersak. Interestingly, Jersak named Chapter 4 Shaking Off the Dust.

Having had my heart cleansed of, and my ego humbled by, the shame of my complicity that can no longer welcome the “gospel of peace”, I have moved on. Truly. And this is where “shaking the dust off our feet” makes new sense to me. The dust we carry is none other than attachments to our former way of being— the ways our resentments still keep us hooked to who we were and anyone or any group that reminds us of that old self.

For others, it's different. The dust they need to shed may be the festering wounds of broken relationships or abusive leaders and how they can become an identity. Wouldn't it be nice if “done” was just a label describing a corner of our life story, rather than an embittered identity that never lets us leave our hurts? In this regard, are we talking about leaving people, leaving family, leaving communities? Understandably, sometimes that's necessary for one’s spiritual, mental, and emotional health. (Jersak, page 46)

Reader, that’s quite profound, isn’t it?

I’m listening to Nick Cave on YouTube as I write this. Wild God has finished and Ghosteen has begun to play. The song Hollywood has come on, We crawl into our wounds, sings Nick Cave, whose 15 year old son Arthur fell off a cliff and died in 2015. Cave wrote and composed the Ghosteen album in the depths of his grief for his son.

Writes Cave in The Red Hand Files, at times Ghosteen may feel unmoored and homeless, but it is pointed firmly toward paradise, the crew is joyous, the world smiles, and the sun bursts over the edge of the earth (20.3.2020).

Reader, shaking the dust off our feet feels like the thing we do when we have decided to crawl out of our wounds, doesn’t it? I imagine crawling out of my wounds, covered in the dust of wound exudate. The dust we carry is none other than attachments … the festering wounds … [that have or threaten to] become an identity, writes Jersak.

“Shake off the dust,” says Jesus.

I tell him, “Look, Jesus, we don't just shake off trauma.” (Jersak, p. 46)

Jersak reminds us with vivid imagery, that the sh1t stench does linger, because, indeed, we cannot easily shake off trauma. Unfortunately, we can leave a dangerous social environment without leaving behind the dust of our attachments to it—we may still live out our days in the bitterness of our narratives. (Jersak, p. 47).

Jersak goes on to quote Felicia Murrell, who writes about the brutal and beautiful work of separating the humans who’ve hurt us from the story we’ve woven about them. Reader, we knit these narratives about the people who wounded us, we knit a giant narrative blanket and we wrap ourselves in this thing we’ve created for ourselves, stitch by stitch, with the actions and attitudes of others which we’ve captured for some kind of sick and misguided posterity. Reader, I know that we do this as an act of self-soothing.

The work of healing becomes unbinding ourselves, doesn’t it? Healing demands that we unwrap ourselves from this weighted blanket of hurtful narratives. It demands that we unravel the hurtful stuff that’s keeping us warm and bitter. Felicia reminds herself, “I will not live trapped in a story of my own making.” Indeed. How do we unwrap ourselves from the blanket of sh1t we’ve so devotedly woven for and wrapped around ourselves? How do we exit the trap we’ve erected around ourselves? How do we shake that dust off our feet? It’s akin to birthing ourselves, reader.

Reader, doesn’t the exercise of healing sometimes feel like an exile from ourselves? In this week’s Torah parsha, Naso, we learn about the Gershonites, the clan whose tasks involve labour and porterage. Gershon the name has its etymology in the Hebrew word for driving out or expulsion — the root being גָּרַשׁ, garash. Zohar Atkins writes about exile becoming a vocation in this week’s Shabbat Reading.

The Gershonites teach us that poetic and holy work involves moving a familiar burden to an unfamiliar place. And even when that burden seems slight or marginal, it makes all the difference. — Zohar Atkins, 7.06.2025)

In the gospel, Jesus Himself frequently retreated from civilisation. He chose to exile Himself in the wilderness to grieve and meditate after the murder of His cousin John the Baptist, for instance. When He arrived at His remote destination, Jesus chose to minister to the sick and suffering and hungry. In His bid for spiritual liberation from human grief and trauma, Jesus chose exile, and He met others burdened with suffering, as He sought to shake the dust from His feet.

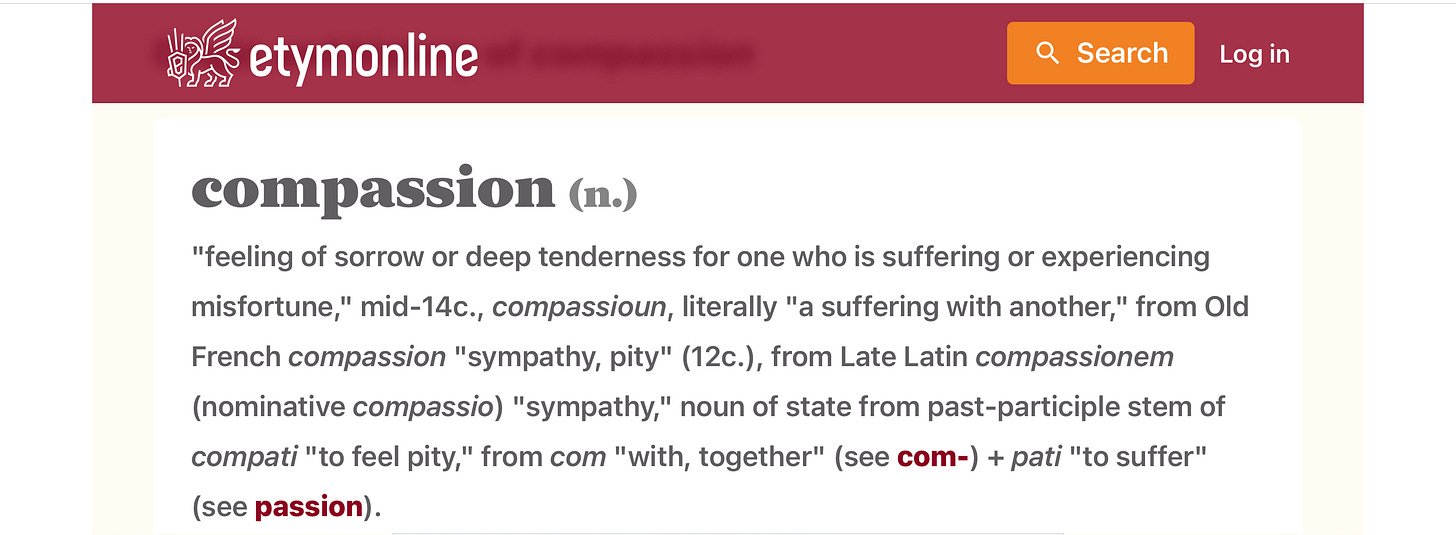

So, reader, all of this to say that, whilst we cannot rewrite or undo the trauma, we can rewrite the narrative we’ve crafted in response to the trauma. We can see as redemptive the things that hurt us and trapped us in a stinky bondage. Exodus can become emancipation. Like bnei yisrael, we might sometimes feel overwhelmed and exasperated and impatient, and momentarily wish to crawl back into our wounds. That’s the human condition. Feelings aren’t facts and they aren’t gods, they’re our messengers, they’re our invitations to pause and regroup. Through compassion we can embrace ourselves, accept what we cannot change, and change the things that rest within our power to change.

So, reader, take my hand, let’s walk each other home. Shake the dust off your feet. Be-leave.

Great article!

Being named back to back with Nick Cave is humbling. Thanks for the shout-out and seeing the convergence!