Gudrun Himmler + the Banality of Evil

reclaiming the word Nazi for actual Nazism

At the tender age of 15 young Gudrun Himmler’s world turned upside and collapsed when the allies defeated Nazi Germany. To me, in my world, the defeat of Nazi Germany seems like a good thing; to Gudrun, in her world, it seems like the end of everything, like the oxygen got sucked from her life, leaving her in a vacuum. This research into denazification and the children of Nazis often leaves me with gaping and irritating sadness because of these observations I make about the Human Condition that I find difficult to juxtapose. In the season that marked celebration and happiness for my own mother, who celebrated her 14th birthday in May of 1945, clear across the world in a completely alternate reality a young girl around the same age faced the most devastating things a child can face.

Before now, it never occurred to me to think of the fall of the Third Reich as personally tragic for individuals. When you live on the side of the victorious you tend to focus very little or not at all on the “not-victorious”. With the Holocaust, a segment of society for many years designated humanising the enemy as defying convention — we don’t want to know about the monsters who did the atrocities, we said smugly during that era. Society punished Arendt for pointing out the obvious about evil. Speer got released from Spandau, the nice Nazi got everyone’s attention. Could evil really be banal? Could it really be that uncomplicated?

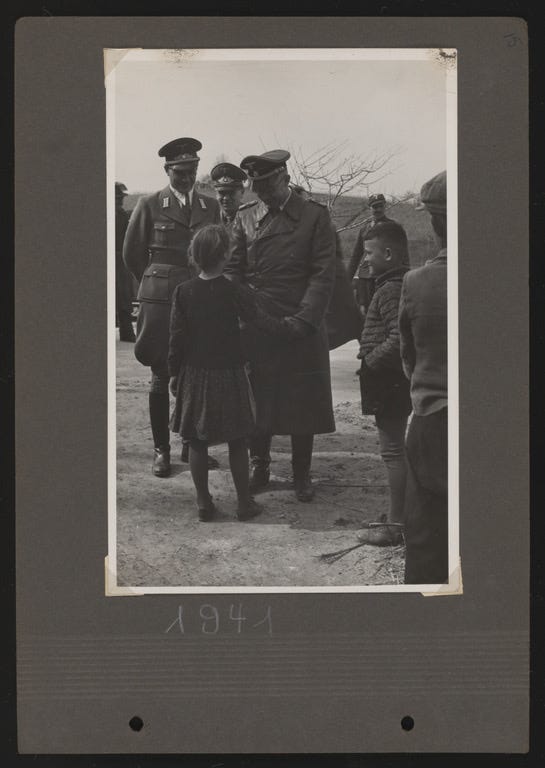

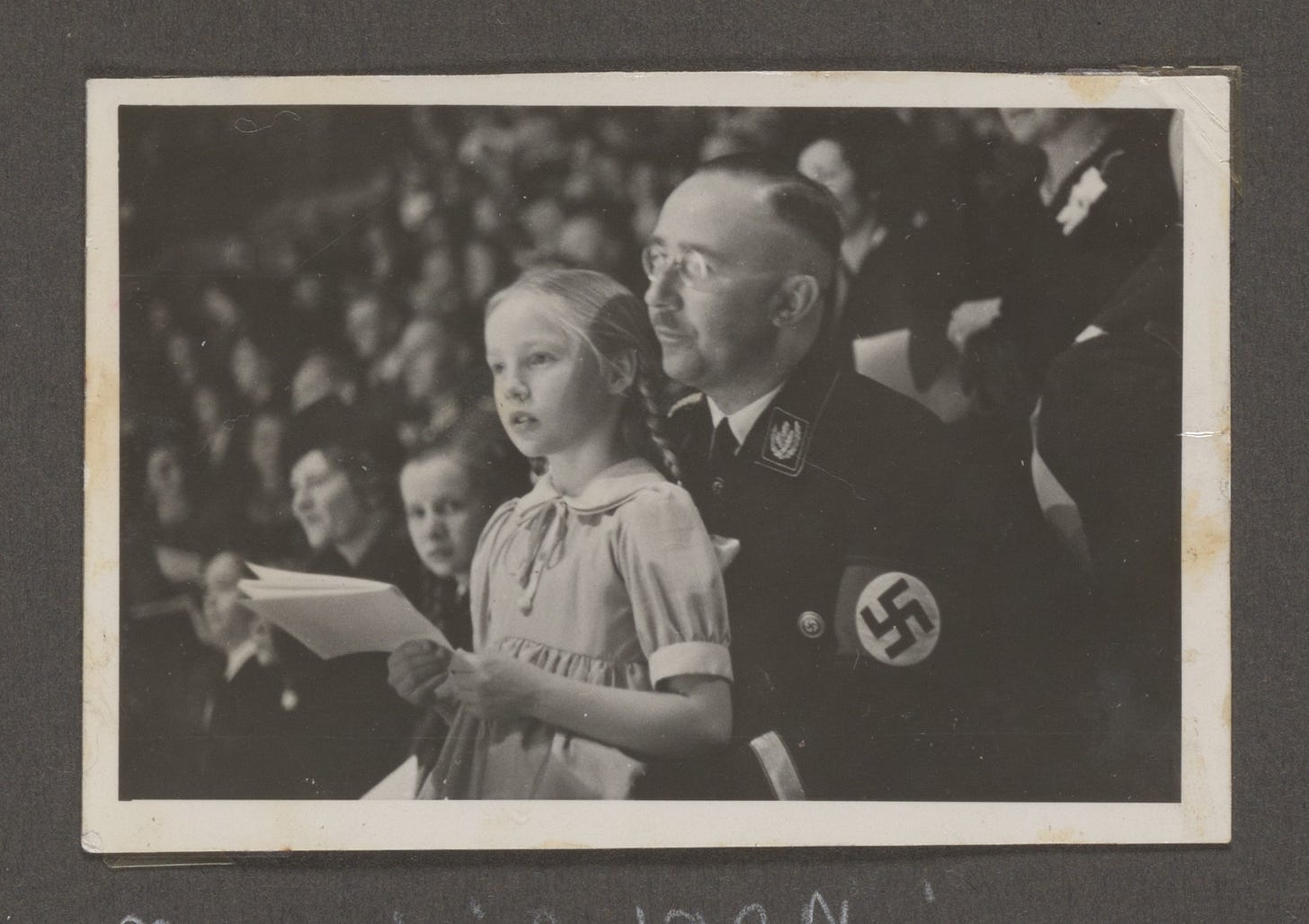

Three days after capture by the British, Gudrun Himmler’s father killed himself, having been on the run for weeks as a fugitive and war criminal. This man who put on a great show of doting upon his only legitimate daughter, took himself out. Heinrich left his beloved Püppi with the unbearable and horrid burden of his crimes. He left his beloved Püppi with the knowledge that her whole relationship with her Pappi amounted to a lie—the pretense of an empty narcissistic + mediocre + monstrously banal man. How does a child carry the weight of her father’s crimes? How does a child carry the weight of her father’s abusive past? How does a child love a father who lived a secret life as a horrible devilish entity? How does a child love a father who caused mass suffering and death? How does a child forgive herself for loving such a father?

Heinrich Himmler bit into a cyanide capsule on May 23, 1945 whilst in British custody somewhere in the NW of Germany. Margarete Himmler, whom the British had arrested 10 days earlier with daughter Gudrun, tried to shield her daughter from the awful news. Journalist Anna Stringer reported that she had never witnessed such emotional emptiness as she observed in Frau Himmler on learning about her husband’s death. News of Heinrich’s death by suicide plunged an adolescent Gudrun Himmler into a severe psychiatric breakdown. For 3 weeks she languished in extreme delirium and physical illness, all much to the chagrin of the British Officer assigned to Gudrun and her mother. From a practical perspective, Himmler’s wife and child held little strategic interest for the allied forces, who did not have the resources to manage such complex + challenging care. Remember the allies did not expect what greeted them when they liberated Germany and German occupied territories. No one could imagine.

After studying her early life and reading about her bond with Heinrich, I believe that, if Gudrun would overcome the dark hell of her father’s crimes, it would happen in these three weeks. Gudrun remained a convinced Nazi for her entire life, yet I cannot feel any contempt or anger toward her. No, I can only feel pity and a deep sadness for her. How on earth does a child have a chance to live any semblance of normalcy when her father has masterminded and overseen the industrial scale slaughter of 16 to 20 million people? How can I, who adored my father (not a mass murderer or any kind of bad man), and struggled to face his few minor flaws after his death, fault Gudrun or any other child of a Nazi for the way they choose to come to terms with their fathers’ lives? How does a child love a parent who has committed monstrous and awful acts that have caused widespread suffering? How does the world come to understand that a connection between parent and child defies earthly morality and logic and convention because it happens independently of all these?

I have known many people who struggled to come to terms with a dad who was a sh1tty man, including those who had to come to terms with their father trying to kill their mother — how does a young lad grow into a man who looks just like the one who beat him senseless as a child and tried to take his mother’s life?

My own living sisters struggled to face decisions our mother had to make, decisions that no mother ought to face, decisions made in and which resulted in unspeakable suffering. The three of us came from the same mother and yet we did not, how did my sisters learn to carry the past so it didn’t break them in the present? How interesting that I have picked up a thing to study which they finally could put down, now that mum has died and opened that story up and closed it also.

We cannot comfortably enter into adulthood without slaying these dragons, we only find comfort when we have tamed or slayed them—that’s the human condition.

Gudrun emerged from her delirium convinced that her father could not have committed the cowardly act of suicide, committed to the story that the British must have assassinated him. Gudrun denied her father’s culpability. In fact, throughout her life Gudrun Himmler had a dream: to restore Heinrich Himmler’s reputation to its former Nazi glory. Gudrun remained a true believer in Nazism and she stayed completely committed to a mythical image of her father she built her entire adult life inside, until her death at age 88.

The tragedy of Heinrich Himmler’s crimes extends to the impact they had on his daughter, who cannot be held responsible for things her father did when she was a child, no matter how revolting the views she held in her adulthood. During the war Heinrich saw his daughter a total of 15 times, each time for a maximum of a few days at a time. To continue my comparison—my mum saw her dad daily, so in 1945 mum saw pépère 15 times in 6 days not 6 years! Furthermore, Heinrich didn’t love Gudrun’s mother, having shacked up with a mistress in town, where he secretly made a new life with his new young family out in the open. Heinrich wrote Gudrun and her mother regularly, sending her photos of himself and with packages of sweets and books and other gifts of hard to acquire during wartime items.

Reading Margarete’s diary I get the sense she really thinks he intends to come back to her, that work and not lovelessness keeps him away. She cannot bear to write otherwise. The reality of his increasing absence grows over time, like a dark cloud around her diary entries. Until Margarete finds out about Heinrich’s mistress in early 1941. As the reality of Heinrich’s weakness as a husband and father closes in on Margarete, she becomes more irascible.

When I read about Gudrun’s early life, the abject amorality and cruel narcissism of the grownups, especially the men, strikes me like a large + hot coal in the forehead at high velocity. This apathy and narcissism of adults, the supposed caregivers of children, feels harsh and jarring next to young Gudrun’s adoration and unconditional love. She was a child. They were children. The thoughtlessness of zealous adults just savages my psyche in ways I cannot yet describe. I think of my connection to my own father, I cannot imagine that I would react any differently than Gudrun did, were someone to have told me he was one of the worst mass killers of the modern era.

How does a child handle such a monstrous thing?

Gudrun’s story raises the question, how does a child judge her father’s crimes? How can we judge our parents? What is meant by the commandment that calls us to honour your mother and father? How do you honour your father when he is one of the worst mass murders in modern history? Does loving an evil father make the child evil?

Gudrun had a lopsided connection with her father. As mentioned above, during the war she saw Heinrich a total of 15 times. How many times did you see your dad in any 6 year period of your young life? I saw my dad every day, he left at dawn and he returned at dusk, and you could set your clock by his schedule, steadfast and reliable was he. Gudrun had no such luxury, despite her privileged upbringing. She adored a doting and faithful and honourable dad who didn’t really exist except in letters and phone calls and all the things Heinrich never told her. My dad didn’t write me fancy letters, he did show up for me, for everything, for always. What is loving your child? As childhood changes how does parenting change? What does parenting demand from us?

What story are you telling yourself, asks Gabor Maté? It’s a profound question, what story do we tell ourselves about our origin, or childhood, our parents? Gudrun chose to create a story about her father that she could live with, she climbed inside that story and she lived her whole life there. Martin Bormann Jr believed it possible to separate the man who was his father from the man who worked as Hitler’s top aide.

Niklas Frank believes his duty to truth and the Holocaust victims means he must hate his father. Rather than run away from, Niklas ran toward the knowledge of his father’s crimes. Niklas Frank sought to know and understand everything and he remained angry at his parents and the German public who went along with the crimes against humanity. I see the unrelenting and intense hatred Niklas has for his father as a distortion of his love for his dad. Sometimes an obsessive revulsion like this masks a deep wound and reflects a longstanding feeling of betrayal, often extreme hate for one’s parents is love spiced with an existential rage that’s a vindaloo level of intensity.

There are as many ways to come to terms with the crimes and sins of parents as there are children. I do not judge what I do not know, how could I? In the end the banality of evil disturbs me the most.

My father was a man of incredible honor, love and loyalty. You're probably referring to the Jews. No conversation about Nazism is complete without talking about the Jews and the crimes they were said to have been victims of. I was often with my father, including during the war, and if there was a government plan to kill the Jews, I would have heard about it, albeit by accident. I heard my father give the order to make life in the transit and prison camps as pleasant and bearable as possible for the prisoners.

I heard him talk about the Jews being freed after the war and relocated either to Palestine, Madagascar or deep into Russia, from where they had come to Europe several hundred years ago. Understanding who these people are is key to solving a nation's problems. They have distinct racial characteristics such as dark hair, hooked noses, large ears and beady eyes, and while they may appear European to some degree, they work to destroy what Europeans have religiously and culturally built up. —Gudrun Himmler-Burwitz